An Ongoing Study of the Origins of the Alaskan Husky

A Deeper History of

the Origins of The Alaskan Husky

A study in progress, By Stephanie Little Wolf

~Click photos for larger view~

TerminologyFor the purposes of this paper I have used the term Alaskan Husky to refer to any animal of husky looks, born and bred in Alaska to pull in harness, with its genetic history primarily founded by Alaskan Native Dogs, from either or both interior village bloodlines or coastal Eskimo dog bloodlines.

I use the term sled dog to describe any dog that pulls in harness for any application and racing sled dogs to describe any dog bred specifically for speed and endurance, used to compete in sled dog races. This terminology may or may not be shared by other mushers.

Most people I have been around simply refer to sled dogs as sled dogs and then later in the conversation it becomes more specific about types, bloodlines and usage. Most sled dogs in Alaska are a conglomeration of Alaskan Husky and other breeds that have been added and selected for what ever use a particular musher has.

The Alaskan Husky

My descriptions and analysis of the history of the Alaskan Husky probably differs from many articles of late. It is based less on modern racers opinions and knowledge of the modern history of sled dog racing, (which is readily available in numerous publications), and instead is more focused on an interest in and study of the early history and prehistory of Alaskan dogs. This complex topic is consistently left out of, or skipped over with a brief word or single sentence, in discussions concerning the beginnings of our sled dogs here in Alaska. The simple fact is however, that native dogs have been here in Alaska for thousands of years, and they form the genetic base of our modern Alaskan Husky.

The history of the Alaskan Husky starts in no other place than prehistory, that is, the vast time before Europeans and Russians came to North America, and with the Native Village Dogs that once populated this region. Indeed, no discussion of Alaskan dogs would be complete without at least the mention of Pre-Columbian Native Dogs in North America, of which there were a huge variety of size, description, and type. Several careful scientists are at work to understand the nature of this aspect of prehistory. Prominent researchers are, R.K.Wayne, Jennifer Leonard, Susan Janet Crockford, Juliet Clutton-Brock Marion Shwartz, N. Nakarmura, Stanley Olsen, Roe, Caries Vila, Peter Savolainen, and many others. Their areas of study cover many disciplines: Anthropology, Archeology, Archeozoology, Migration, Biology and Genetic research.

Tal Tan Bear Dogs |

Coastal Eskimo Dogs, and the Alaskan Interior Village dogs, are the two largest groups of native dogs that make up the base of the Alaska Husky. Both are descended from pre-Columbian dogs which crossed the Bering Straits in wave after wave of migration with pre-columbian peoples starting as early as 14,000 years ago or before. Indeed, scientists have determined that the Bering Land Bridge was intact both 35,00 years ago and 20,000 years ago. These hardy animals were fully domesticated dogs according to recent DNA research and were primarily descended from central or east Asian wolves, although some genetic studies show that certain native dogs were isolated for extreme periods of time and may have evolved from or mixed with local wolf populations of which they shared a genetic heritage. (1)

Dogs were crucial in varying degrees to many tribal groups across North America, and were used for many important tasks, such as packing heavy loads in the summer, and dragging supplies on snow in the winter as the nomadic peoples of Alaska traversed from place to place. Dogs were also used for hunting and tracking. Dogs were companions and babysitters, as well as early warning systems for bears, enemies, or other forms of danger. Most nomadic peoples did not selectively breed these dogs unless unwanted puppies were culled for a variety of reasons. (2) Like most nomadic tribal peoples, castration was not practiced until the turn of the century, and selection was based on need, not looks.

As sledding technology made its way into the interior regions, tribal peoples began to hunt, trap, fish, and race with dogs that pulled sleds. They began to breed dogs purposely that could run faster for village races, although the dogs still had to work and hunt as well. The dogs looked like huskies, well furred up and strong-but not the fox like Siberians. Some regions had more of a larger dog and others had smaller more slender or rangy animals. Natural selection was still very much in place. Coastal village or Eskimo dogs were robust, heavy boned, and could survive on little food and very little water. At times they were only fed in winter, and left free to care for themselves in summer, sometimes kept on islands and fed only occasionally. They had tightly curled tails, large heads, and thick well furred coats. They were and are to this day capable of terrific feats of strength, helping to haul large chunks of whales across the sea ice to be further butchered. These were the types of dog that were witnessed by explorer Martin Forbisher in 1577, and later in 1897 by Fridtjof Nansen. (3)

Interior dogs sometimes had short half or broom tails, were of a more slender or rangy nature than Eskimo dogs. Unlike dogs of the lower forty eight, they were photographed briefly before becoming totally amalgamated by European and Siberian breeds. Some of these photos can be viewed on VILDA, the Alaskan digital archive of museum photographs. It is also helpful to research the Horse Creek Mary image, as this photograph from the turn of the century depicts two wonderful examples of Interior (Atnha) Village dogs. Although Coastal Eskimo dogs have been preserved in today's Inuit sled dog, Canadian Eskimo dog, and Greenlander- the Interior Village dogs are a thing of the past. It would take an extensive and prolonged archeological and accompanying genetic study to determine just how much original strain remains in any of today's Alaskan Village dogs, as outside dog breeds came to Alaska during the Gold rush and have added to the Alaskan Husky make up. Miners tried their hand at copying the Eskimo dog as they became more in demand by breeding the Saint Bernard and Newfoundland to captive female wolves. The results were not probably what they expected as most high content hybrids would rather work out the pecking order than work as a team. Any Large dog that could pull a load was added to the mix. Lots of people came to Alaska during the gold rush, bringing and breeding dogs for hauling huge loads of supplies. Mail run dogs were also kept for hauling the mail, up to 700 lb loads of mail were pulled by dogs. Indeed, they had to be hardy.

Siberian Husky was added to much of the Interior Alaskan dog population when Leonard Seppala with his Siberian imports, entered the scene. These dogs were fast and racy compared to the larger slower Eskimo dogs and other large mixed breed dogs, and the new dogs became popular for their hardiness, happy natures and hard work ethic. Continuing with Roland Lombard in the 1920's and 30's, racing with Siberians became all the rage, and many of these dogs were taken to villages and mixed with the native village dogs. Like the Alaskan Malamute, eventually Siberian Huskies became the product of closed stud books and ridged AKC standards. Today, one can still see strong Siberian blood in many Alaskans, as those lines continue to be favored by some mushers. In addition to AKC Siberian Huskies, Racing Seppala Siberians are sometimes favored by sprint mushers, or simply a part of the genetic heritage of their racing dogs. Its ironic that those dogs have now become inbred to the point that some Seppala breeders are now backcrossing with Alaskan Huskies.

Hounds, pointers, and Irish Setters were experimented with early on. One can view photographs of the famous "Balto" to see an example of an early mixed breed husky-hound or pointer racing dog. He certainly resembles some of the racing dogs of today. All of these breeds made their way to villages in Alaska, and into to the village dogs that remained.

Racing Sled Dogs

All of these dogs also made their way into toady's racing sled dog, a mix of the evolving village dog along with its famous Siberian background, have continued to receive admixtures of greyhound as big mid distance and distance racing experienced resurgence in Alaska in the 1970's.

Now days Pointer and even Saluki have been experimented with in racing kennels. The new Eurohound is a choice for many sprint mushers. A Eurohound is a cross between an Alaskan Husky and German Short haired Pointer. This cross first successfully entered the competitive sled dog racing world in Scandinavia. It is one of the most formidable racing dogs in the world, combining the husky's centuries-honed sledding ability and a pointer's enthusiasm and athleticism. I have also seen Border Collies and other breeds added recently.

Egil Ellis with his team of Scandinavian Hounds winning the World Cup in Ostersund, Sweden, 1998 |

What is lost and what is gained for the dogs? Short coats and a different personality, lack of toughness of bone structure, quality of feet, inability to live outside and withstand cold etc. are some of the problems I have had related to me from some mushers, in associated with breeding in European bloodlines for speed alone. Some mushers complain of a lack of mental toughness as well. Some sled dog racing kennels have to keep their dogs inside a heated barn and the animals have to wear coats when they run. I have also witnessed many, many dogs at the local sprint track picking up their feet, as they shiver to keep them warm one at a time. They may love to run, but they certainly don't enjoy the climate! Still other dogs who have managed to retain some sort of coat, seem to do fine in the far north chill. Whatever bloodlines they sport, whether distance or sprint, racing sled dogs are the best at what they do, and they do it magnificently. Some of them are huskies and some are not, some are a carefully blended mix that just wants to run, run, and run.

All Alaskan Huskies share certain qualities, many of them still do fall primarily into the Husky category, occasionally even

resembling the village dogs. They all are an

amazing lot of dogs living in an amazing environment with an unusual lot of dog lovers who

love to hit the trail and get a run in. They leap and bark, scream and lunge into their

harnesses. I tend to prefer dogs who resemble Village Dogs as much as possible, especially

from the great Yukon River villages, from both here in Alaska and in British Columbia. Now

days its rare to hear a musher exclaim that a dog is "Villagey" or, an Native

Elder tell me that a dog is "Old Timey". Those old dogs were really something in

their ability to work in a variety of different applications. And they were indigenous to

this great land. An animal shaped by great amounts of time and isolation, which was still

the product of natural selection, an animal that tribal people and nature had already

perfected for this extreme climate and cultural life. I strive to protect that ideal in my

dogs, how much I am succeeding would take a detailed genetic and archeological study.

Meanwhile, I really enjoyed Mary Shields description of the Alaskan Husky best, and it

goes something like this: The Alaskan sled dog,(Husky), is a conglomeration of

bloodlines constantly evolving to meet to the evolving needs of the mushers who breed

them. (Season of the Sled Dog,

1989, Mary Sheilds

resembling the village dogs. They all are an

amazing lot of dogs living in an amazing environment with an unusual lot of dog lovers who

love to hit the trail and get a run in. They leap and bark, scream and lunge into their

harnesses. I tend to prefer dogs who resemble Village Dogs as much as possible, especially

from the great Yukon River villages, from both here in Alaska and in British Columbia. Now

days its rare to hear a musher exclaim that a dog is "Villagey" or, an Native

Elder tell me that a dog is "Old Timey". Those old dogs were really something in

their ability to work in a variety of different applications. And they were indigenous to

this great land. An animal shaped by great amounts of time and isolation, which was still

the product of natural selection, an animal that tribal people and nature had already

perfected for this extreme climate and cultural life. I strive to protect that ideal in my

dogs, how much I am succeeding would take a detailed genetic and archeological study.

Meanwhile, I really enjoyed Mary Shields description of the Alaskan Husky best, and it

goes something like this: The Alaskan sled dog,(Husky), is a conglomeration of

bloodlines constantly evolving to meet to the evolving needs of the mushers who breed

them. (Season of the Sled Dog,

1989, Mary Sheilds

Notes:

(1) ANCIENT DNA EVIDENCE OF A SEPARATE ORIGIN FOR NORTH AMERICAN INDIGENOUS DOGS Ben Koop, Maryann Burbidge, Ashley Byun, Ute Rink, Susan J. Crockford Bar books: DOGS THROUGH TIME: AN ARCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE Eighth Congress of the International Council for Archeology, A Symposium on the History of the Domestic Dog, Victoria, B.C. 1998

(2) A good exception to this is the Salish Wooly dog Susan Janet Crockford, 1997 (3) Travelers of the Cold, by Dominigue Cellura

Resources:

1) Dogs of the American Aborigines- Allen, Glover Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard College Vol. 43, #9 Cambridge, Mass, 1920

2) Dogs of the Northeastern Indians, Butler and Hancock Mass. Archaeological Society Bulletin vol. 10, #2 pages 17-35, 1949

3) From Dogs to Horses among the Western Indian Tribes, F. G. Roe, Transactions, royal Society of Canada, third series, Volume xxx111 1939

4) A History of Dogs of the Early Americas, By M.Schwartz Yale University Press 1979

5) Lost History of the Canine Race M.E. Thurston, chapter 7 "The Other Americans" (page 146) Andrews and McMeel, 1996

6) First Nations, First Dogs B.D. Cummins, Canadian Ethnocynolgy Destilig Enterprises, Alberta Canada, 2002.

7) Multiple and Ancient Origins of the Domestic Dog Caries Vila, Peter Savolainen, Jesus E. Maldonado, Isabel R. Amorim, John E. Rice, Rodney L. Honeycutt, Keith A. Crandall, Joakim Lundeberg, Robert K. Wayne* (Mitochondrial DNA control region sequences were analyzed from 162 wolves at 27 localities worldwide and from 140 domestic dogs representing 67 breeds. Sequences from both dogs and wolves showed considerable diversity and supported the hypothesis that wolves were the ancestors of dogs. Most dog sequences belonged to a divergent monophyletic clade sharing no sequences with wolves. The sequence divergence within this clade suggested that dogs originated more than 100,000 years before the present. Associations of dog haplotypes with other wolf lineages indicated episodes of admixture between wolves and dogs. Repeated genetic exchange between dog and wolf populations may have been an important source of variation for artificial selection.)

8) Please read this interesting article about the Innu Atumut dogs: http://www.innu.ca/dog1.html

(1) ANCIENT DNA EVIDENCE OF A SEPARATE ORIGIN FOR NORTH AMERICAN INDIGENOUS DOGS Ben Koop, Maryann Burbidge, Ashley Byun, Ute Rink, Susan J. Crockford Bar books: DOGS THROUGH TIME: AN ARCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE Eighth Congress of the International Council for Archeology, A Symposium on the History of the Domestic Dog, Victoria, B.C. 1998

(2) A good exception to this is the Salish Wooly dog Susan Janet Crockford, 1997 (3) Travelers of the Cold, by Dominigue Cellura

Resources:

1) Dogs of the American Aborigines- Allen, Glover Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard College Vol. 43, #9 Cambridge, Mass, 1920

2) Dogs of the Northeastern Indians, Butler and Hancock Mass. Archaeological Society Bulletin vol. 10, #2 pages 17-35, 1949

3) From Dogs to Horses among the Western Indian Tribes, F. G. Roe, Transactions, royal Society of Canada, third series, Volume xxx111 1939

4) A History of Dogs of the Early Americas, By M.Schwartz Yale University Press 1979

5) Lost History of the Canine Race M.E. Thurston, chapter 7 "The Other Americans" (page 146) Andrews and McMeel, 1996

6) First Nations, First Dogs B.D. Cummins, Canadian Ethnocynolgy Destilig Enterprises, Alberta Canada, 2002.

7) Multiple and Ancient Origins of the Domestic Dog Caries Vila, Peter Savolainen, Jesus E. Maldonado, Isabel R. Amorim, John E. Rice, Rodney L. Honeycutt, Keith A. Crandall, Joakim Lundeberg, Robert K. Wayne* (Mitochondrial DNA control region sequences were analyzed from 162 wolves at 27 localities worldwide and from 140 domestic dogs representing 67 breeds. Sequences from both dogs and wolves showed considerable diversity and supported the hypothesis that wolves were the ancestors of dogs. Most dog sequences belonged to a divergent monophyletic clade sharing no sequences with wolves. The sequence divergence within this clade suggested that dogs originated more than 100,000 years before the present. Associations of dog haplotypes with other wolf lineages indicated episodes of admixture between wolves and dogs. Repeated genetic exchange between dog and wolf populations may have been an important source of variation for artificial selection.)

8) Please read this interesting article about the Innu Atumut dogs: http://www.innu.ca/dog1.html

Pre-Columbian Tribal Dogs In The Americas

by Stephanie Little Wolf

~Click photos for larger view~

The dog who first entered North America with paleoindians was a well

established inhabitant along with his human counterpart as early as fourteen thousand

years ago. DNA studies on the genetic structure of paleoamerican dogs show that this was a

fully domesticated animal at the time of entry into the North American continent,

suggesting that the domestication of dogs occurred at an earlier time than has been

previously suggested, (the archaeological record suggests canid domestication events

around fourteen thousand years ago)- about the same time that humans walked over from

Eurasia to the new world. This would indicate that the dog was actually domesticated at an

earlier time than that.

The DNA FactorIndeed, the Mtdna (mitochondrial) studies strongly support the hypothesis that paleoamerican and Eurasian domestic dogs share a common origin, both evolving from the Eurasian gray Wolf. No evidence of a separate domestication of dogs from North American Grey Wolves was discovered. Although the haplotypes found in paleoamerican dogs were closely related to Eurasian dogs, some of them formed a unique clad within the main genetic group, (clad 1), which is found only in paleoamerican dogs. This indicates that dogs were present and isolated in the new world for a considerable amount of time. This long period of isolation led to the appearance of a group of genetic sequences (haplotypes) that are similar but very easily distinguishable from dogs from other parts of the world, or from any modern dog population in America today. Indeed, no surveyed modern population of dogs in the United States carries these unique genetic markers in their DNA. American Indian Dogs were extinct early on by the inbreeding and replacement by European dogs. Only the Eskimo dog has survived. Dna evidence links the Eskimo Dog with the Australian Dingo, the New Guinea Singing dog, and the Shiba Inu. The Mexican Hairless or Xoloitzcuintle was present in the Americas long before Europeans arrived, but the genetic lineage shows extreme mixing with European dogs and may not genetically resemble its pre-Columbian ancestors anymore, although reduced dentition and hairlessness are extremely dominant traits, so the dogs strongly resemble their forbears in appearance.

Dogs, Wolves, and Coyotes

At the time of European contact, American Indians were groups of diverse and widely dispersed nations. It is common yet inaccurate these days for them to be discussed as one single population and their dogs do not escape this inaccuracy. In fact, there were many different types of Indian dogs and they were used for a variety of reasons that were as diverse and unique as the people they inhabited the land with. It is also common for modern researchers to site early explorers from the late 1600's to the late 1800's and their anecdotal interpretations of Indian dogs as being almost impossible to distinguish from the wolf. This is also a common mistake and misinterpretation today. Countless times I have heard children, and adults refer to my Alaskan Village dogs as wolves. In fact, Eskimo dogs, huskies and other sled dogs may have fur and vocalizations that resemble their wolf ancestors, but that is about it. Dogs have a shorter stockier build, wider chests and shorter faces and muzzles, with short steep "stops" or angle from forehead to the bridge of the nose.

In all, many dogs filled rolls within Indian cultures. Some tribes had rather loose associations with their dogs, some were extremely attached and involved with dogs as pets and or using them for various tasks. Dogs probably tracked game, and packed meat after a hunt. Dogs were eaten by some groups as a food source and some were only consumed ceremonially. Dogs were the playmates of young children and companions to the elders.

Four distinct types of tribal dog are presented here, although many more existed at one time. I encourage one to carefully review the list of resources presented at the end of this article.

Great Plains Dogs

Dogs were an integral and important aspect of the tribes they were a part of. It is logical to discuss "dog culture" as the time period before the acquisition of the horse, and the time after this acquisition as "horse culture" by nations of the Great Plains. Some dogs were used for hauling and packing, pulling the famous travois across the plains. They packed meat or belongings, children and the elderly. They were pets, a food source, and possible trackers of game. They were numerous, partly fended for themselves, and bred freely with little input or selectiveness from tribal people. Selective breeding most likely did not occur among plains tribes, the only intervention in this respect was the culling of small or sickly pups or those that were snappish or surly with small children. Culling was also practiced to reduce the load of pups on the mother so she retained her health during the nursing period, and to select for large heavily boned individuals. Dogs served the important function of barking to alarm the tribe of the approach of enemies or visitors.

Large and medium sized dogs coexisted and are sometimes vicariously referred to as Plains Indian Dogs and Sioux Dogs. These dogs according to some descriptions were either Dingo tawny colored and short or smooth coated, or grayish and somewhat longer coated. Many other color combinations existed, however, such as white, black, spotted and mottled. In reading many of the descriptions, what comes across is an animal somewhat like a dingo and somewhat like a husky. Tails were either short, broom or half tails, or sickle shaped with the typical curve of many a pariah dog throughout the world today. Photographs that exist of plains Indians and dogs show extremely mixed individuals, in recreated scenes that tried to depict a lifestyle well after cultural demise. The dogs bear the mark of European breeds, in color, coat texture; many possessing the typical heavier flopped over ears.

The Tahl Tan Bear Dog

This little bear

dog was from 12 to 18 inches tall and weighed from 10- to 18lbs. Amazingly, It survived

into the late 1960's or early 70's. This dog of the Tlingits, Tahltans, Kaska, and Sekani

was used for hunting bears in British Columbia, Canada. The hunters carried the dog inside

a pouch until bear tracks were discovered, where upon the dogs tracked the bear. These

small dogs could run on top of crusty snow and bark and worry the bear until hunters

arrived. These little dogs were black with white markings, or white with black markings,

not much bigger that today's Schipperke. On examining a photograph from Atlin, B.C., of a

bear dog, I noticed its resemblance to the New Guinea Singing Dog, an extremely rare dingo

type dog from Papua New Guinea. In another photograph, the dog resembled a Papillion.

This little bear

dog was from 12 to 18 inches tall and weighed from 10- to 18lbs. Amazingly, It survived

into the late 1960's or early 70's. This dog of the Tlingits, Tahltans, Kaska, and Sekani

was used for hunting bears in British Columbia, Canada. The hunters carried the dog inside

a pouch until bear tracks were discovered, where upon the dogs tracked the bear. These

small dogs could run on top of crusty snow and bark and worry the bear until hunters

arrived. These little dogs were black with white markings, or white with black markings,

not much bigger that today's Schipperke. On examining a photograph from Atlin, B.C., of a

bear dog, I noticed its resemblance to the New Guinea Singing Dog, an extremely rare dingo

type dog from Papua New Guinea. In another photograph, the dog resembled a Papillion. The Eskimo, or Inuit Dog of Canada, Alaska, and Greenland: The Qimmiq

Today, the Eskimo dog thankfully is alive and well. It originally occupied the coastal and archipelago areas of Greenland, Alaska, and Canada. Once upon a time, today's Malamute fell into the Eskimo dog category, the indigenous dog of the

Mahlemuit Eskimos from the Kotzebue Sound area in

Alaska. The Eskimo dog was a puller of sleds, used for hauling heaving loads of fish,

whale, and seal or walrus from the hunt to the village or camp. In the summer, backpacking

was the traditional use of the dog. The dogs are bigger and more heavily boned than

Siberian Huskies, which are not native to North America. They could and can work in the

most hostile of environments with little food or care. They are friendly for the most part

but fight with each other to establish the ritual pecking order. They are primitive

compared to most modern breeds, as they don't bark as much and howl often. They have heavy

winter coats and range from as small as 45 lbs for females to as large as 85lbs for males,

sexual dimorphism being related to more primitive qualities. An Eskimo dog's fur or pelage

takes many colors, but the eyes should not be blue and there is some controversy here.

These dogs are challenging to work with and are strong beyond belief with incredible

stamina. They are known in modern times as The Canadian Inuit Dog, The Inuit sled dog, and

the Greenlander or Greenland dog. Clubs and organizations today are strong enthusiasts for

the Eskimo dog, getting together and employing the old style fan hitch to go dog sledding

or the modern tandem hitch for those of us who have narrow forest trails.

Mahlemuit Eskimos from the Kotzebue Sound area in

Alaska. The Eskimo dog was a puller of sleds, used for hauling heaving loads of fish,

whale, and seal or walrus from the hunt to the village or camp. In the summer, backpacking

was the traditional use of the dog. The dogs are bigger and more heavily boned than

Siberian Huskies, which are not native to North America. They could and can work in the

most hostile of environments with little food or care. They are friendly for the most part

but fight with each other to establish the ritual pecking order. They are primitive

compared to most modern breeds, as they don't bark as much and howl often. They have heavy

winter coats and range from as small as 45 lbs for females to as large as 85lbs for males,

sexual dimorphism being related to more primitive qualities. An Eskimo dog's fur or pelage

takes many colors, but the eyes should not be blue and there is some controversy here.

These dogs are challenging to work with and are strong beyond belief with incredible

stamina. They are known in modern times as The Canadian Inuit Dog, The Inuit sled dog, and

the Greenlander or Greenland dog. Clubs and organizations today are strong enthusiasts for

the Eskimo dog, getting together and employing the old style fan hitch to go dog sledding

or the modern tandem hitch for those of us who have narrow forest trails.The West Coast Salish, Little woolly Dog or Clallam Indian Dog

These dogs were restricted to a fairly distinct area of northern British Columbia, where they were kept on islands to keep them from breeding with other types of dogs. The responsibility of woman, they were small, somewhat larger than todays Pomeranian. They had had a long thick mostly white pelage which was harvested by the Salish Indians to make clothing and blankets from. The dogs were numerous and highly utilized. Vancouver recorded that the dogs were shorn to the skin like sheep, and that the shorn wool of the dogs was so thick, that large mats of it could be lifted without being pulled apart. The wool of these dogs was dyed red or blue and striped blankets of cedar strips and dog wool were hardy and warm. The Artist Paul Kane gives us a wonderful and lengthy description of how the dog wool was made into blankets using cedar and white earth, apparently twisted together a beaten mixture of these, then rolling them down the leg as if twisting twine or yarn, then sewing the strips together.

Other Native American Dogs

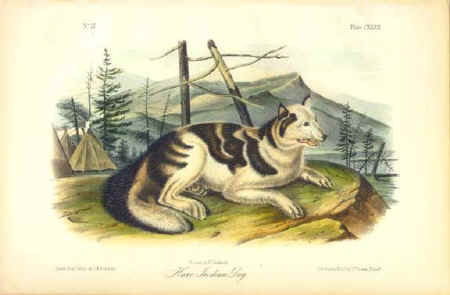

There were many other dogs of North and South America. The Peruvian Pug-nosed dog, the Feugian dog, the Inca dogs, the Xoloytzecuintli, or Mexican hairless dog, the Hare Indian dog of the north, the Short Nosed dogs of the southwest, to name just a few. It is sad that most of these dogs are gone, with the exception of the Xolo, and Mexican Hairless. I have acquired photographs of Mayan dogs and they may resemble original Mayan dogs somewhat in their similarity to pariah type or aboriginal dogs from other parts of the world.

The Archaeological record tells us that native pre-Columbian dogs were often buried with their owners, and at other times, given their own intricate burials. They disappeared rapidly, and with good cause, unable as their owners were to withstand European dog diseases, and probably shot as a matter of course for their attention to European livestock. On the east coast among the original colonies of America, Indian dogs were outlawed and it was a crime for villages to possess them, as it was firearms. One needs only compare the demise of the pure Australian Dingo as a model for how fast native dogs disappeared from north, central, and South America. In Australia, only small pockets of genetically pure Dingoes remain, and they are threatened. One can openly imagine how fast North American dogs became amalgamated from their pure forms, and then disappeared entirely from the lives of a people whose own lives became increasingly difficult. It was all tribal nations could do to manage their own fates in the face of rapid decimation. Unlike the Dingo, dogs of the Americas had no wild populations from which to replenish their numbers. In their absence, we must turn to scientific research and learn what we can about this fascinating subject.

Resources on Native American Dogs

Studying modern aboriginal dogs such as the Dingo, the Santal Hound, and the New Guinea Singing dogs may shed some light on the relationship between native tribal peoples and their dogs. Following, is a list of resources which reveals a wonderful and interesting topic of study. In addition to these sources, I encourage one to study the works of R.K. Wayne, Jennifer Leonard, Susan Crockford, I. Lehr Brisbin, Janice Koler -Matznik, and Bulu Imam.

1) Leonard J. A., R. K. Wayne, J. Wheeler, R. Valadez, S. Guillén and C. Vilà.

Ancient DNA evidence for Old World origin of New World dogs.

Science 2002; 298:1613-1616.

2) Dogs of the American Aborigines- Allen, Glover

Bulletin of the Museum pf Comparative Zoology, Harvard College

Vol. 43, #9

Cambridge, Mass, 1920

3) Dogs of the Northeastern Indians, Butler and Hancock

Mass. Archaeological Society Bulletin

vol. 10, #2

pages 17-35, 1949

4) From Dogs to Horses among the Western Indian Tribes, F. G. Roe,

Transactions, royal Society of Canada, third series, Volume xxx111

1939

5) A History of Dogs of the Early Americas,

By M.Schwartz Yale University Press

1979

6) Lost History of the Canine Race

M.E. Thurston, chapter 7

"The Other Americans"

(page 146)

Andrews and McMeel, 1996

7) First Nations, First Dogs

B.D. Cummins, Canadian Ethnocynolgy

Destilig Enterprises, Alberta Canada, 2002

Stephanie Little Wolf is a singer, songwriter, poet and

research technician. She attended Cabrillo Junior College, and graduated from The

University of California, Santa Cruz in 1996.

Stephanie Little Wolf is a singer, songwriter, poet and

research technician. She attended Cabrillo Junior College, and graduated from The

University of California, Santa Cruz in 1996. Her studies and interests include DNA research, Anthropology, Archeology, and Sociology, pre-Columbian life in North America and the development and domestication of the dog in prehistory.

She has lived and worked in Alaska for many years, preserving her family's bloodline of sled dogs which she inherited in 1989.

She has worked with Native Alaskan foster children and her sled dogs, developing a healing environment for abused and neglected children as they learn to care for and run sled dogs.

In addition to her work with children and dogs, Stephanie has worked with Native non-profit organizations in Alaska to preserve Athabascan culture and language, and has followed this up with a pocket dictionary project at the Alaskan Native Language Center, at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, where she worked to preserve the Lower Tanana Dialect of the Athabascan language family.

No comments:

Post a Comment